In the late 1980s many trout fisheries in the West were in peril. Something called whirling disease was found in many streams, including Wyoming. Some of the impacts were devastating for trout populations, including in two states that border Wyoming — the Colorado River in Colorado and the Madison River in Montana.

This rainbow trout has a cranial deformity that is indicative of whirling disease. (WGFD photo)

“Nobody in the western United States knew about whirling disease until Colorado and Montana began seeing devastating declines in some of their best wild trout fisheries,” said Kevin Gelwicks, Wyoming Game and Fish Department assistant fisheries management coordinator and long-time researcher of whirling disease.

The whirling disease parasite was first detected in Wyoming in 1988 in the upper portion of the North Platte River and later in the upper stretches of the Laramie River. The start of the whirling disease parasite in the North Platte River can be traced to a private fish hatchery in Colorado that stocked a number of waters in Wyoming at the time.

Gelwicks said over several years of monitoring, fisheries personnel began finding the whirling disease parasite throughout the state. However, there were no declines in trout populations. Today, several waters in Wyoming have the parasite, which is harmless to humans.

But that doesn’t mean Game and Fish is ignoring whirling disease. In fact, the department has worked to prevent it from impacting fish in Wyoming and is looking into if the disease is preventing fish from thriving in some waters around the state.

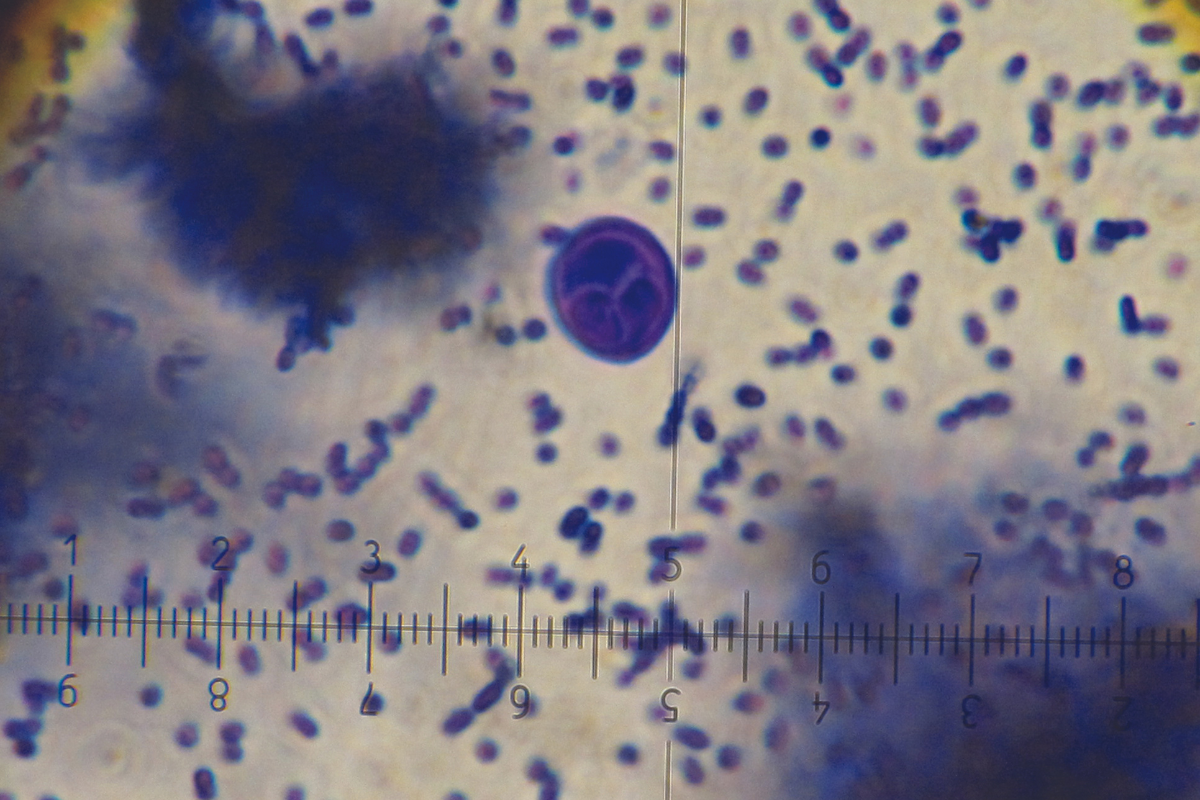

A microscope slide stained with crystal violet shows the presence of Myxobolus cerebralis spores.

WHAT IS WHIRLING DISEASE?

This disease is caused by a microscopic parasite called Myxobolus cerebralis and can be found in trout and other fish in the salmonid family. Once the parasite infects young trout, it feeds on cartilage in the skull. This affects the fish’s nervous system and equilibrium, which causes fish to swim in circles and appear to chase their tail. Fish also may have spinal deformities and blackened tails, which are caused by pressure on nerves that control pigmentation.

The parasite requires two host species to complete its life cycle — a fish and a tubifex worm — a small worm also known as the sludge or sewer worm. These worms ingest sediments, selectively digest bacteria and absorb molecules through their body walls. They can survive with little oxygen and can exchange carbon dioxide and oxygen through their skin — similar to frogs.

When a fish is infected with the parasite and dies, spores from the parasite are released and eaten by tubifex worms, which live in sediments of water bodies. Spores transform into another stage of the parasite called a triactinomyxon, which is expelled by the tubifex worm. Fish get whirling disease from free-floating parasites in infected water.

Younger fish are more susceptible to whirling disease than older fish. Older fish that become infected, along with younger fish that survive the disease, will carry the parasitic spores for the remainder of their lives. Finding the parasite that causes whirling disease doesn’t always mean the fish have the disease, and all fish with the parasite do not have the disease.

Gelwicks said for whirling disease to have a big impact on trout, a lot of factors have to come together at the same time and place. Young fish need to be emerging from their spawning beds at the same time the parasite is emerging from tubifex worms. And, they need to be downstream of the worms producing the parasite. Gelwicks said whirling disease issues in the Colorado River showed up below Windy Gap Reservoir by Granby, which is shallow, silty and had a lot of tubifex worms.

Rainbow trout are the most susceptible to whirling disease, followed by cutthroat, brook and brown trout. Brown trout are more tolerant to the disease because their ancestors evolved with the parasite in Germany. The whirling disease parasite originated in Europe.

Recent research has shown that if the host fish are removed, the life cycle of the parasite is broken and the whirling disease parasite can eventually be eliminated from a body of water.

This rotary filter ultraviolet light water treatment unit was installed at Wigwam Rearing Station to kill potential whirling disease parasites from the hatchery's water source.

SHIFTING OF PRIORITIES

Over time, Game and Fish’s emphasis on whirling disease moved to its fish culture system in the early 2000s. This wasn’t just for whirling disease, but all fish-related diseases, viruses and bacteria.

The effort was led by Steve Sharon, the department’s fish culture supervisor, who retired in 2018 after more than 40 years with Game and Fish and 20 years as the fish culture supervisor. Game and Fish spent millions of dollars upgrading and, in some cases, renovating fish hatcheries around the state.

However, Wyoming’s hatcheries were not immune to whirling disease. In the early 2000s, the Dubois Hatchery and Wigwam Rearing Station got the parasite, and renovations were required to get rid of it. The Ten Sleep and Story hatcheries also had the whirling disease parasite in the past, and renovations at both took place around 2010. Story relies on an open water source from a creek, and since 2010 has been a broodstock facility only.

Whirling disease is not vertically transmitted, which means it can’t be transmitted from the parent to the egg. Adults with whirling disease are always euthanized by a certain age, but the progeny they produce are parasite-free.

Game and Fish tests all of its hatcheries and rearing stations for fish diseases and pathogens once a year.

Travis Trimble, Game and Fish assistant fish culture supervisor, said whirling disease is always a concern, like many other fish pathogens.

“The causative agent for whirling disease is still one that our fish hatcheries take very seriously and monitor for through annual fish health inspections,” Trimble said. “Whirling disease is still considered a pathogen of concern, and if found in one of our hatcheries could result in a complete depopulation for that facility.

“Fish health is held in a very high regard, and I don’t see us going away from that anytime soon.”

Wyoming Game and Fish Department personnel electroshock a portion of the North Tongue River in search of fish to analyze to see if they have whirling disease. (Photo by Christina Schmidt/WGFD)

LOOKING AHEAD

“Whirling disease is on our radar, but in general, we’re lucky that we don’t have a ton of fish health concerns in Wyoming,” Gelwicks said.

Gelwicks said Game and Fish has seen decreased trout populations in some streams around the state. The department isn’t sure if that's caused by whirling disease, but it wants to find out.

For instance, there have been declines in rainbow trout numbers in the North Tongue River in northern Wyoming in recent years. Extensive monitoring in the late 1990s and 2000s showed there was no whirling disease parasite present. However, it is there now.

“It makes us wonder,” Gelwicks said.

A trout from the North Tongue River in the Sheridan Region is measured and other data is recorded. (Photo by Christina Schmidt/WGFD)

The parasite also has been recently documented in the Tongue River, South Tongue River and Middle Fork Powder River.

A project this summer by a Colorado State University graduate student may provide some explanation of the impact of whirling disease in one stream in southwest Wyoming.

Attempts to reintroduce native Colorado River cutthroat trout in LaBarge Creek in southwest Wyoming have been ongoing for more than 20 years. Results have been mixed, but recently the whirling disease parasite was found in the watershed. The study this summer involves placing young cutthroat trout in cages throughout the watershed to see if and where disease impacts may be occurring. These researchers also will be collecting similar information in the North Tongue River to see if the disease is impacting that population.

“Since the whirling disease parasite was discovered in Wyoming more than 35 years ago, we haven’t seen impacts to any of our major trout fisheries,” Gelwicks said. “However, that doesn’t mean Wyoming is immune and impacts could be discovered in the future.”

Wyoming benefits from pristine stream systems, but if a stressor moves in this disease or any disease could take off. Stressors can include changes in habitat, increased sediment and water temperature — all of which can influence whether a fish develops disease.

Proper management could play a role down the road.

— Robert Gagliardi is the associate editor of Wyoming Wildlife