Until recently, the American pika's population in Wyoming was a bit of a mystery. While there have been several targeted studies of pikas in the Cowboy State, previous research has been limited in scale and has focused on populations in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

However, the mounting concerns about the impact of climate change on the pika's habitat and population have brought this issue to the forefront. This prompted petitions in 2007 and 2016 to list the pika under the Endangered Species Act, underlining the need for action.

The Wyoming Game and Fish Department’s nongame section began surveying the state to collect comprehensive data on pika populations within suitable habitat. These initial field seasons served as the beginning of a long-term data collection effort with surveys being conducted several years apart into the future.

The American pika presents unique challenges for biologists to study. Their physiology and dependence on specific geographic and thermal conditions may make them an excellent indicator species for examining the ecological effects of climate change. Changes in pika populations can signal broader shifts in the quality and quantity of alpine habitats. The pika thrives in the rocky, talus slopes of alpine and subalpine regions of the western United States. In Wyoming, pikas are typically found in high-elevation habitats, ranging from 11,000-foot peaks to 8,000-foot rocky hillsides within the central Rocky, Snowy Range and Bighorn mountains. This makes them a less accessible mammal to survey.

These creatures have a high metabolic rate, which helps them stay warm throughout the winter. However, it also makes them susceptible to heat. During summer mornings they cut and pile food from meadows, dry it in the sun and store it for the winter. Once the day warms up, they retreat into the cool spaces between rocks to regulate their body temperature. Unlike many other small mammals, pikas do not hibernate. Instead, they eat their stored vegetation called hay piles, which they rely on to survive the harsh winter months beneath a protective layer of snow. Pikas have a low reproductive rate and limited dispersal ability, primarily because of their intolerance to heat and specific habitat requirements. If they become locally extinct in an area they currently occupy, the extreme isolation of the various Wyoming populations could make recolonization of their habitats difficult.

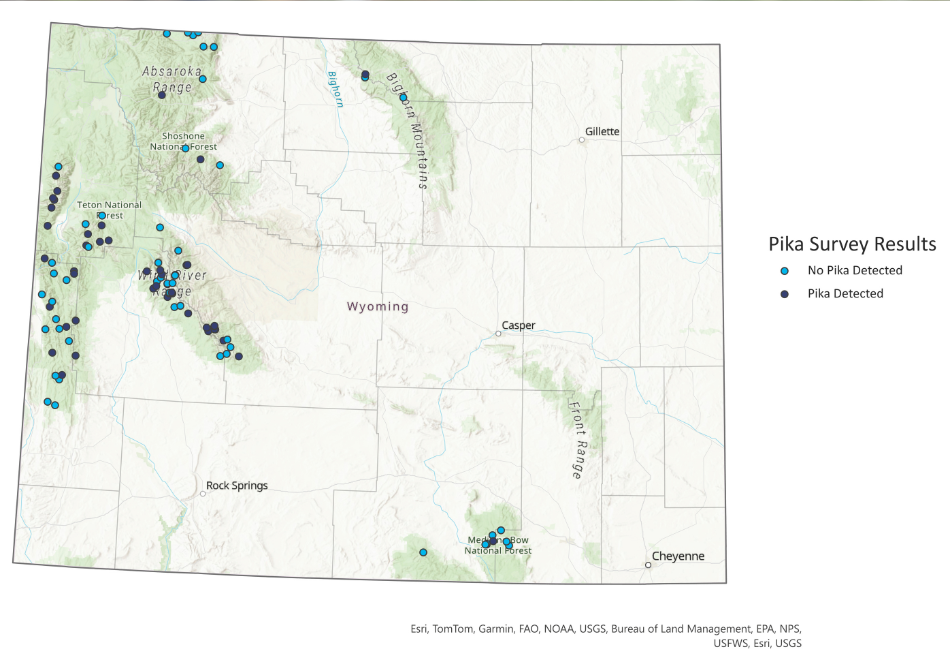

Nongame biologists used aerial imagery to consider habitat suitability and accessibility, and chose survey sites based on an evenly dispersed sample of these potential locations. During the initial summer field seasons of 2020 and 2021, 167 surveys were conducted at 100 unique sites.

“Conducting these statewide surveys was a monumental task, requiring significant time and effort to evaluate site safety and access remote locations. Despite these challenges, the department was able to conduct a baseline survey of 100 sites giving a comparison for future monitoring efforts,” said Zack Walker, Game and Fish Game nongame supervisor.

Surveyors identified pika presence through direct sightings, vocalizations or fresh haypiles. They also gathered details about the habitat, such as the amount of incline, what direction the slope was facing, vegetative cover and site habitat composition. Temperature loggers were installed at random survey sites to examine the relationship between ambient and subsurface temperatures and pika presence or absence.

Over the two survey seasons, observation data estimated 57.1 percent of the suitable modeled habitat in the state was occupied by pika. The collected vegetation, habitat and temperature data are being analyzed to better understand pikas' specific habitat needs. This analysis will help project future changes and inform management strategies.

“The results of occupancy surveys for pika in Wyoming are comparable to surveys conducted in adjacent states,” said Heather O’Brien, Game and Fish nongame mammal biologist. “Our goal now is to repeat these surveys every few years so that we can monitor trends and potential changes. If climate change is having an impact on pikas, we would expect to see occupancy shift to sites at higher elevations and overall occupancy rates to potentially decrease.”

— Rene Schell is the Wyoming Game and Fish Department's information and education specialist in the Lander Region